This is part two of a two-parter. Check out part one.

Empirical methods

The distinction between analytical and empirical methods is that the latter investigates how real users will use the product.

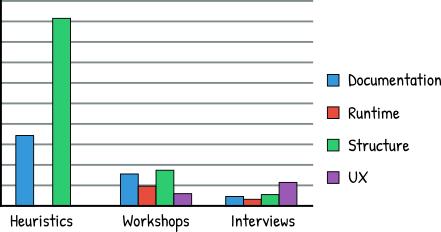

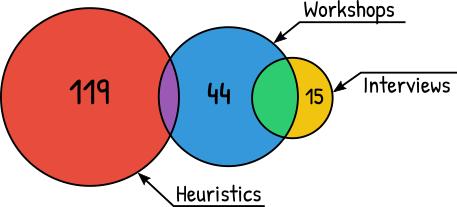

But don’t assume that empirical methods are by default better than analytical: both are important because they discover different problems. This research showed that heuristics were more efficient in finding documentation and structural problems, whereas empirical methods were more useful in finding UX and runtime specific issues.

Monitoring

Monitoring is used to gather usage statistics. For web services, it’s rather easy. For instance, you can discover that one API endpoint is never called. Hence, you should consider the causes: is it missing in the documentation or not needed to anyone? Monitoring also helps to map scenarios: what kind of requests, to which services, and in what order happen most often.

And don’t forget to monitor not only successful requests but also failures. Imagine, some business errors are stockpiling: maybe you need to reconsider API design or error handling?

Another thing to monitor is data volumes. Analysts from the project I worked on assumed that type A documents should be more common than type B documents, so the service was better optimized for the first type. It was quite a surprise when we did a simple SQL count and found out that the number of type A documents were 600 thousand, while type B accounted for 80 million. After that discovery, we had to prioritize tasks related to service B way higher.

Support tickets

If you have a support team, you’re in luck: analyze tickets, pick out those related to usability, and identify the most serious issues. Previously I wrote about accidental Cyrillic symbols instead of English in service schema: these problems resurfaced specifically via support.

Moreover, support tickets offer insight into the most common tools and workflows used to work with your API. Once we had an external developer who generated soapAction dynamically based on a root request structure by trimming the word Request. For example, importHouseRequest gave importHouse. But one of our services with a name importPaymentDocumentRequest expected soapAction=importPaymentDocumentData instead of importPaymentDocument (what the developer would expect). On the one hand, the user’s solution was poor: you’d better use WSDL. On the other hand, maybe they didn’t have a choice and we probably should ask ourselves why naming wasn’t consistent.

Surveys

Not everyone has a support service. Or perhaps it doesn’t give enough information. In that case, surveying API users is helpful. There is no point in giving examples: this topic is highly contextual. But you can start with the basics: “What do you like?”, “What do you don’t like?”, and “What would you like to change?”.

User sessions

User sessions are the most expensive and cumbersome usability evaluation method. You need to find people based on a typical user profile, give them some tasks, watch the process, and analyze results.

Each company administers sessions in its own way. Some perform remote sessions, others invite developers on site. In both cases developers can use their own laptops and favorite IDEs: first, it’s closer to real-world conditions, second, it minimizes stress from an unknown environment.

Yet, there are more exotic examples. A developer is led to the room with a one-way mirror (yup, like in movies). A usability expert sits behind the mirror and observes developer actions as well as what’s happening on the dev’s computer screen. The developer can ask questions, but the expert will answer only in rare cases. In my opinion, it’s too sterile.

Generally, all API related user sessions have two phases. The first phase is a developer workshop with tasks like:

- Solve a problem in the notebook without an IDE (to get an idea of how developers would design API on their own).

- Practical tasks for API usage (e.g., write a code for file upload using a service).

- Read and review a code snippet to assess its clarity and readability (use printouts to make this task more challenging).

- Debug a faulty code snippet (this helps to study how a user will handle and correct an error).

The second phase is an interview where you ask:

- Name three biggest issues you encountered during the workshop and how did you overcome them (documentation, support, StackOverflow, a friend’s help)?

- How much time did you spend looking for additional information outside official documentation?

- Did you encounter unexpected error messages? If yes, did they help you correct a problem?

- Name at least three ways to improve official documentation.

- Name at least three ways to improve API design.

Personas

Personas are used both in analytical and empirical methods. All you need is to figure out which characteristics best describe your users (in case of API, developers). These descriptions tend to be humanized by assigning a name and a photo, adding information about fears and preferences. You can wear a “persona hat” while applying heuristics or rely on them while selecting developers for user sessions.

Typical developers’ personas:

- Systematic developers don’t trust API and write code defensively. They are usually deductive, write on C++, C, or even Assembly.

- Pragmatic developers are more common and work both in deductive and inductive manners. Typically they code desktop and mobile apps in Java or C#.

- Opportunistic developers concentrate on solving business problems in an exploratory and inductive fashion. Guess what language they prefer? JavaScript.

Now, I want to point out that the aforementioned language discrimination is not my invention. If you’re lucky, perhaps you’ll find the original article by Visual Studio usability expert, where these quirky definitions were introduced. Unfortunately, I was able to get only [its first page in the Wayback Machine][visual-studio], so you have to take my word for it. Nevertheless, I hope this example can encourage you to create your own personas.

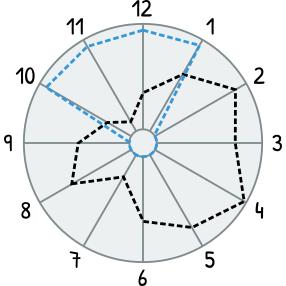

We can also combine personas with cognitive dimensions. Create a radar chart with 12 axes, where each axis is a cognitive dimension. Next, plot current values for your API and values according to the persona’s expectations. This chart is great for comparing how existing API corresponds to user values.

Developer from the example chart (blue line) prefers API with a high level of consistency (10) and hates writing boilerplate (4). As we can see, the current state of API (black line) doesn’t satisfy these criteria.

Summing up

Readers comfortable with GUI usability testing would say: “That’s exactly the same stuff!”. And you’re right, there is nothing supernatural about API usability. Even though it’s called an application programming interface, programs are yet to learn how to find other APIs and use them automatically; they still need us, meatbags. That’s why almost everything applied for GUI usability evaluation is reusable for API with some adjustments.

Now, what about the best method? None, apply them all! According to this research, each method can identify unique issues.

If you are tight on resources, I suggest using the least expensive methods: heuristics, cognitive dimensions, walkthrough, and support tickets. Even the simplest techniques can drive API improvements.

Someone would argue that API usability is not that important: “we don’t have time for that, it’s a dev thingy.” But developers created style guides not just to be fancy; this serves to accelerate the achievement of shippable quality. We care about hidden code quality, therefore we need to care about externally visible code like APIs even more.